North America’s largest recorded earthquake helped confirm plate tectonics

In the early evening of March 27, 1964, a magnitude 9.2 earthquake roiled Alaska. For nearly five minutes, the ground shuddered violently in what was, and still is, the second biggest temblor in recorded history.

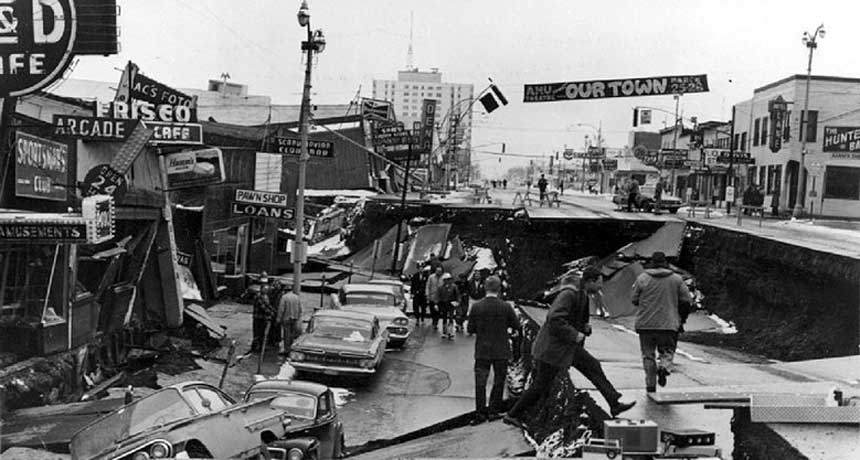

Across the southern part of the state, land cracked and split, lifting some areas nearly 12 meters — about as high as a telephone pole — in an instant. Deep, house-swallowing maws opened up. Near the coast, ground turned jellylike and slid into bays, dooming almost everyone standing on it. Local tsunamis swamped towns and villages.

Not many people lived in the newly formed state at the time. If the quake had struck in a more developed place, the damage and death toll would have been far greater. As it was, more than 130 people were killed.

In The Great Quake, Henry Fountain, a science journalist at the New York Times, tells a vivid tale of this natural drama through the eyes of the people who experienced the earthquake and the scientist who unearthed its secrets. The result is an engrossing story of ruin and revelation — one that ultimately shows how the 1964 quake provided some of the earliest supporting evidence for the theory of plate tectonics, then a disputed idea.

Using details from his own interviews with survivors — along with newspaper articles, diaries and other published accounts — Fountain focuses his story on two places near Prince William Sound. More people died in the port of Valdez (a familiar name because of the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill) than in any other Alaskan community, while the small village of Chenega suffered the highest proportional loss of life. Fountain’s tracking of the myriad small decisions people made that fateful day — that either put them in harm’s way or kept them safe — is meticulous. The experiences of the survivors and the lost are haunting.

Interwoven with stories of the human tragedy is Fountain’s account of the painstaking scientific gumshoe work necessary to piece together how such a monster earthquake had occurred. That’s where George Plafker, a geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, comes in. In surveying the quake’s aftermath, Plafker, along with others, noticed something strange: There was no surface evidence of a fault large enough to explain the colossal shaking or the widespread uplift and sinking of land over hundreds of thousands of square kilometers.

Today, scientists know that Earth’s outer layer is divided into giant pieces and that the motion of tectonic plates — as they bump together or slide past each other — helps explain how some earthquakes occur. But in the mid-1960s, plate tectonics was just a hypothesis in need of real-world validation.

Plafker’s crucial contribution was to realize that the powerful Alaskan quake had no surface fault because it took place at what is now known as a subduction zone, where dense oceanic crust sinks under lighter continental crust. The insight into the quake’s origin provided some of the first real proof of tectonic plate movements.

Throughout the book, Fountain weaves in brief histories of key people and ideas in the development of the theory of plate tectonics. For those familiar with the history, Fountain doesn’t offer much new. People less familiar may find it a little difficult to keep one geologist straight from another geophysicist.

But The Great Quake is an elegant showcase of how the progressive work of numerous scientists over time — all the while questioning, debating, changing their minds — can be pieced together into an idea that reshapes how we see and understand the planet.