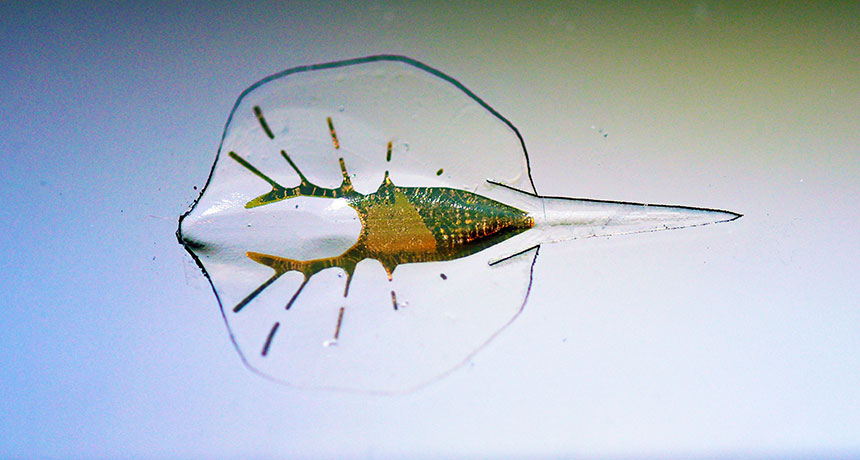

Light-activated heart cells help guide robotic stingray

Even robots can use a heart. Or heart cells, at least.

A new stingray bot about the size of a penny relies on light-sensitive heart cells to swim. Zaps with light force the bot’s fins to flutter, letting researchers drive it through a watery obstacle course, Kit Parker of Harvard University and colleagues report in the July 8 Science.

The new work “extends the state of the art — very much so,” says bioengineer Rashid Bashir of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “It’s the next level of sophistication for swimming devices.”

For decades, the field of robotics has been dominated by bulky, rigid machines made mostly of metal or hard plastic. But in recent years, some researchers have turned toward softer, squishier materials, such as silicones and rubbery plastics (SN: 11/1/14, p.11). And a small group of scientists have taken it one step further: combining soft materials with living cells.

So far, there’s just a handful of papers on these hybrid machines, says Bashir, whose own lab recently reported the invention of tiny, muscle-wrapped bots that inch along like worms in response to light.

In 2012, Parker’s team built a robotic jellyfish out of silicone and heart muscle cells. Electrically stimulating the cells let the jellyfish push itself through water by squeezing its body into a bell shape and then relaxing.

But, Parker says, “the jellyfish just swam.” He and his colleagues couldn’t steer it around a tank. They can, however, steer the new stingray.

He explains the team’s strategy with a story about his daughter. When she was little, Parker would point his laser pointer at the sidewalk and she’d try to stomp on the dot. He could guide her down a path as she followed the light. “She got to be independent and I got to make sure she didn’t step out into traffic.”

Parker guides his stingray bot in a similar way.

Layered on top of the bot’s body — a gold skeleton sandwiched between layers of silicone — lies a serpentine pattern of cells. The pattern is made up of about 200,000 these cells, harvested from rat hearts and then genetically engineered to contract when hit with pulses of blue light.

Flashing the light at the bot sets off a wave of contractions, making the fins undulate, like a flag rippling in the wind. To make the stingray turn, the team stimulates the bot’s right and left fins separately. Faster flashing on the right side makes the ray turn left and vice versa, Parker says.

By moving the lights slowly across a fluid-filled chamber, the researchers led the bot in a curving path around three obstacles.

“It’s very impressive,” says MIT computer scientist Daniela Rus. The stingray is “capable of a new type locomotion that had not been seen before” in robots, she says.

Bashir says he can envision such devices one day used in biomedicine or even environmental cleanup: Perhaps researchers could program cells on a swimming bot to suck toxicants out of lakes or streams. But the work is still in its early days, he says.

Parker, a bioengineer interested in cardiac cell biology, has something entirely different in mind. He wants to create an artificial heart that children born with malformed hearts could use as a replacement. Like a heart, a stingray’s muscular body is a pump, he says, designed to move fluids. The robot gave Parker a chance to work on assembling a pump made with living materials.

“Some engineers build things out of aluminum. I build things out of cells — and I need to practice,” he says. “So I practice building pumps.”

There’s another upside to the robot too, he adds: “It’s cool and fun.”