Lungs enlist immune cells to fight infections in capillaries

Immune cells in the lungs provide a rapid counterattack to bloodstream infections, a new study in mice finds. This surprising discovery pegs the lungs as a major pillar in the body’s defense during these dangerous infections, the researchers say.

“No one would have guessed the lung would provide such an immediate and strong host defense system,” says Bryan Yipp, an immunologist at the University of Calgary in Canada. Yipp and his colleagues report their findings online April 28 in Science Immunology.

The work may offer ways to target and adjust our own immune defense system for infections, says Yipp. “Currently, we only try to kill the bacteria, but we are running out of antibiotics because of resistance.”

The research uncovers some of the mechanisms that drive the rapid activation of neutrophils, says immunologist Andrew Gelman of Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. “This is critical in removing bacteria from sequestered spaces in the lung,” he says.

Generally, clearing bacteria out of the bloodstream falls to macrophages that reside in the liver and the spleen. But macrophages aren’t found in vessels of the lungs. So the lungs’ blood vessel network gives pathogens a place to hide and escape the body’s usual removal efforts.

In mammals, neutrophils hang out in the lungs’ bloodstream more than in blood vessels that wind through other tissue. Past research has indicated that a dearth of neutrophils puts an individual at risk for a bloodstream infection. It wasn’t clear, though, how they were providing a defensive role in the blood, says Yipp.

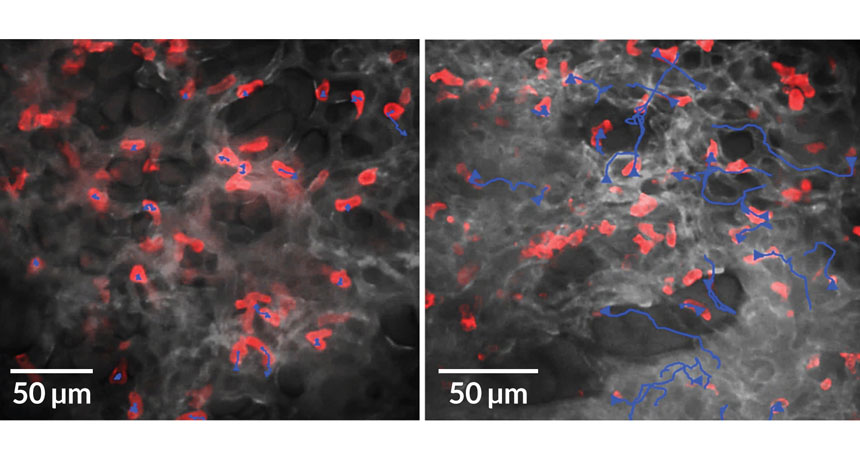

Yipp and his team used confocal pulmonary intravital microscopy to view how cells and pathogens behave in living mouse lungs. The researchers found that about a third of the neutrophils seen in the mouse lung sample were crawling about three to four cell lengths along the walls of the capillaries, the smallest blood vessels in the lungs. When the researchers added LPS, a molecule found in the cell wall of gram-negative bacteria like Escherichia coli, almost all of the neutrophils began crawling, and they traveled more than twice as far as before.

One of the proteins needed for neutrophil crawling, CD11b, allows the immune cells to move along as though on a tank tread, says Yipp. After LPS was added, the neutrophils in a mouse lung deficient in CD11b crawled about a third of the distance as the neutrophils in a normal mouse lung.

In another experiment, the researchers injected fluorescent E. coli into a mouse. Within 10 minutes of the bacteria reaching the lungs, the neutrophils started to crawl toward the bacteria and gobble them up, a process called phagocytosis. The neutrophils captured the majority of the bacteria within an hour of injection, says Yipp.

Gelman says it’s now clear that neutrophils are good at removing bacteria from the lungs’ capillaries. The next step is to “show the actual biological impact” — how this system controls a bacterial infection and improves survival, he says.

For patients with depressed immune systems, the finding may eventually provide a way to battle bloodstream infections, Yipp says. But, he notes, “with all infections, part of the concern is that the inflammatory response can become too exuberant, which leads to tissue damage, as in septic shock,” and lung failure. In those cases, learning how to dampen the lungs’ immune response could help, Yipp says.