Virus triggers immune proteins to aid enemy

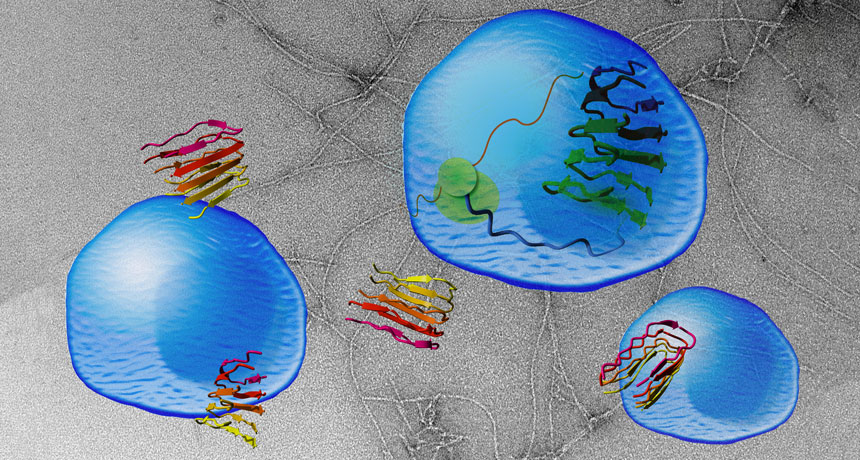

Crucial immune system proteins that make it harder for viruses to replicate might also help the attackers avoid detection, three new studies suggest. When faced with certain viruses, the proteins can set off a cascade of cell-to-cell messages that destroy antibody-producing immune cells. With those virus-fighting cells depleted, it’s easier for the invader to persist inside the host’s body.

The finding begins to explain a longstanding conundrum: how certain chronic viral infections can dodge the immune system’s antibody response, says David Brooks, an immunologist at the University of Toronto not involved in the research. The new studies, all published October 21 in Science Immunology, pin the blame on the same set of proteins: type 1 interferons.

Normally, type 1 interferons protect the body from viral siege. They snap into action when a virus infects cells, helping to activate other parts of the immune system. And they make cells less hospitable to viruses so that the foreign invaders can’t replicate as easily.

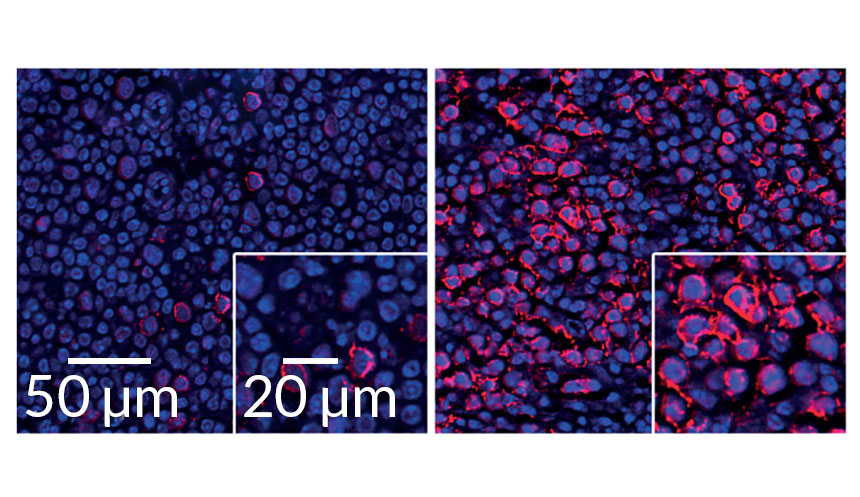

But in three separate studies, scientists tracked mice’s immune response when infected with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, or LCMV. In each case, type 1 interferon proteins masterminded the loss of B cells, which produce antibodies specific to the virus that is being fought. Normally, those antibodies latch on to the target virus, flagging it for destruction by other immune cells called T cells. With fewer B cells, the virus can evade capture for longer.

The proteins’ response “is driving the immune system to do something bad to itself,” says Dorian McGavern, an immunologist at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke in Bethesda, Md., who led one of the studies.

The interferon proteins didn’t directly destroy the B cells; they worked through middlemen instead. These intermediaries differed depending on factors including the site of infection and how much of the virus the mice received.

T cells were one intermediary. McGavern and his colleagues filmed T cells actively destroying their B cell compatriots under the direction of the interferon proteins. When the scientists deleted those T cells, the B cells didn’t die off even though the interferons were still hanging around.

Another study found that the interferons were sending messages not just through T cells, but via a cadre of other immune cells, too. Those messages told B cells to morph into cells that rapidly produce antibodies for the virus. But those cells die off within a few days instead of mounting a longer-term defense.

That strategy could be helpful for a short-term infection, but less successful against a chronic one, says Daniel Pinschewer, a virologist at the University of Basel in Switzerland who led that study. Throwing the entire defense arsenal at the virus all at once leaves the immune system shorthanded later on.

But interferon activity could prolong even short-term viral infections, a third study showed. There, scientists injected lower doses of LCMV into mice’s footpads and used high-powered microscopes to watch the infection play out in the lymph nodes. In this case, the interferon stifled B cells by working through inflammatory monocytes, white blood cells that rush to infection sites.

“The net effect is beneficial for the virus,” says Matteo Iannacone, an immunologist at San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Milan who led the third study. Sticking around even a few days longer gives the virus more time to spread to new hosts.

Since all three studies looked at the same virus, it’s not yet clear whether the mechanism extends to other viral infections. That’s a target for future research, Iannacone says. But Brooks thinks it’s likely that other viruses that dampen antibody response (like HIV and hepatitis C) could also be exploiting type 1 interferons.