New questions about Arecibo’s future swirl in the wake of Hurricane Maria

When Hurricane Maria’s 250-kilometer-per-hour winds slammed into Puerto Rico on September 20, they spurred floods, destroyed roads and flattened homes across the island. A week-and-a-half later, parts of the island remain without power, and its people are facing a humanitarian crisis.

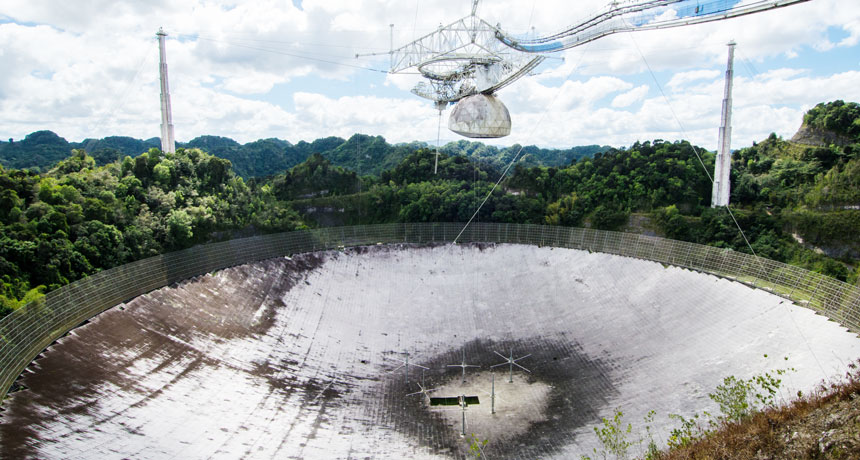

The storm also temporarily knocked out one of the best and biggest eyes on the sky: the Arecibo Observatory, some 95 kilometers west of San Juan. The observatory’s 305-meter-wide main dish was until recently the largest radio telescope in the world (a bigger one, the FAST radio telescope, opened in China in 2016).

As news trickled out over the past week, it appeared that the damage may not be as bad as initially reported. The observatory is conserving fuel, but plans to resume limited astronomy observations September 29, deputy director Joan Schmelz tweeted earlier that day. “#AreciboScience is coming back after #MariaPR.”

But the direct whack still raises the issue of when – and even whether – to repair the observatory: Funding for it has repeatedly been on the chopping block despite its historic contributions to astronomy.

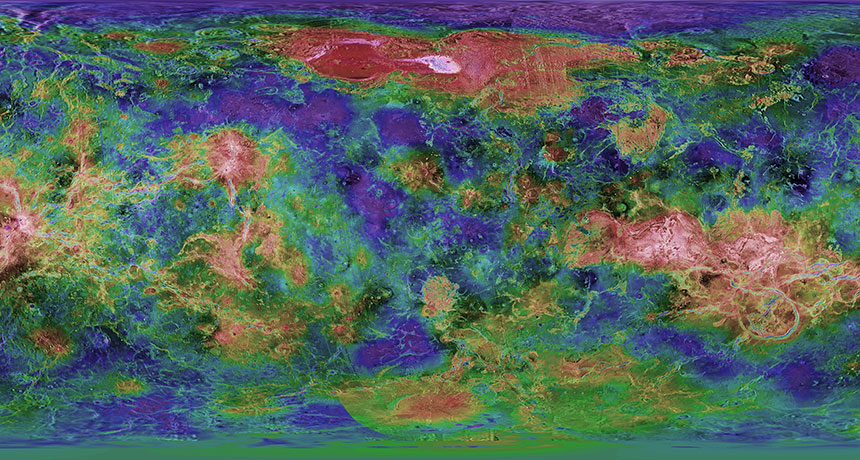

Arecibo’s recent work includes searching for gravitational waves by the effect they have on the clocklike regularity of dead stars called pulsars; watching for mysterious blasts of energy called fast radio bursts (SN Online: 12/21/16); and keeping tabs on near-Earth asteroids.

It played a key role in the history of the search for extraterrestrial intelligence: In 1974, astronomers Frank Drake, Jill Tarter and Carl Sagan used it to send messages to any extraterrestrial civilizations that might be listening (SN Online: 2/13/15). It was also the telescope that, in 1992, discovered the first planets outside the solar system.

Arecibo also holds a special place in my personal history: Watching actress Jodie Foster use the giant dish to listen for aliens in the movie Contact when I was 13 cemented my desire to study astronomy. I chose to go to Cornell University for undergrad in part because the university managed Arecibo at the time, and I hoped I might get to go there. (I never did, but my undergrad adviser, Martha Haynes, uses Arecibo to study the distribution of galaxies in the local universe.) And one of the first science stories I ever had published was about Cornell professors testifying to the National Science Foundation, which owns Arecibo, to defend the observatory’s funding.

Ten years after that story ran in the Cornell Daily Sun, Arecibo’s funding situation is still in doubt. It’s not clear how the recent damage will affect its future.

Telescope operator Ángel Vázquez sent the first damage reports via short-wave radio on September 21. A line feed antenna, used to receive and transmit radio waves to study the Earth’s ionosphere, broke off and fell onto the observatory’s main dish, damaging some of its panels. A second, 12-meter dish was thought to have been destroyed entirely.

But the smaller dish survived with only minor damage. “Initial reports said it had just been blown away, but it turned out that was not correct,” says Nicholas White of the Universities Space Research Association, which co-operates the observatory with SRI International, a nonprofit headquartered in Menlo Park, Calif., and Metropolitan University in San Juan, Puerto Rico. “That looks like it’s fine, although obviously we have to get up there and check it out.”

On September 23, observatory director Francisco Córdova posted a picture to the observatory’s Facebook page of two staff members standing in front of the big telescope dish with an outstretched Puerto Rican flag. “Still standing after #HurricaneMaria!” the post declares. “We suffered some damages, but nothing that can’t be repaired or replaced!”

The line feed antenna is a big loss, but it should be replaceable eventually, White says. And the damage to the main dish is fixable. Among the tasks was to get inside the Gregorian dome — the golf ball‒like structure suspended over the giant dish — and make sure the reflectors within it were aligned correctly. (Those reflectors were knocked askew by Hurricane George in 1998, says Cornell radio astronomer Donald Campbell.)

Meantime, Arecibo staff, who managed to safely shelter in place during the storm, “have been showing up for work, funnily enough,” White says. “People just want to get back to normal.”

But normal is also a state of uncertainty. The NSF, which foots $8.3 million of the observatory’s nearly $12 million a year operating costs, has been trying to offload their responsibility for it for several years. (NASA covers the balance.) And NSF’s agreement with the three groups that jointly maintain and operate the observatory runs out in March 2018. In 2016, the NSF called for proposals for other organizations to take over after that.

The NSF can’t estimate yet how expensive the repairs will be or how long they will take to complete, so it’s reserving comment on how the damage will affect decisions about the observatory’s future. “We need to make a complete assessment,” says NSF program director Joseph Pesce.

Personally, I hope the observatory remains open, both for science and for inspiration. I’m still waiting for a reply to that 1974 Arecibo message.